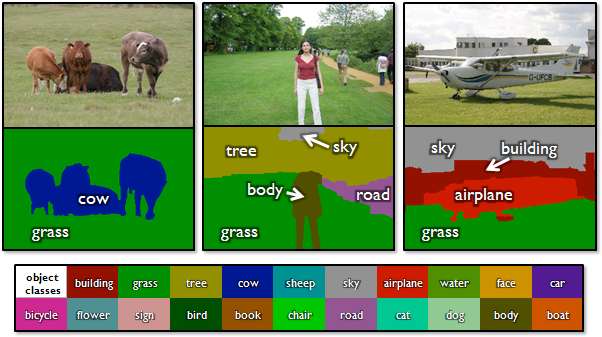

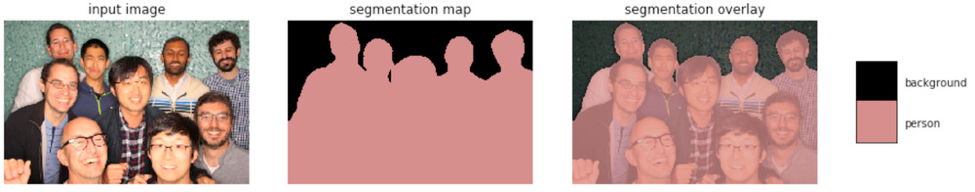

This week, we continue the NeuroNuggets series with the fifth installment on another important computer vision problem: pose estimation. We have already talked about segmentation; applied to humans, segmentation would mean to draw silhouettes around pictures of people. But what about the skeleton? We need pose estimation, in particular, to understand what a person is doing: running, standing, reading NeuroNuggets?

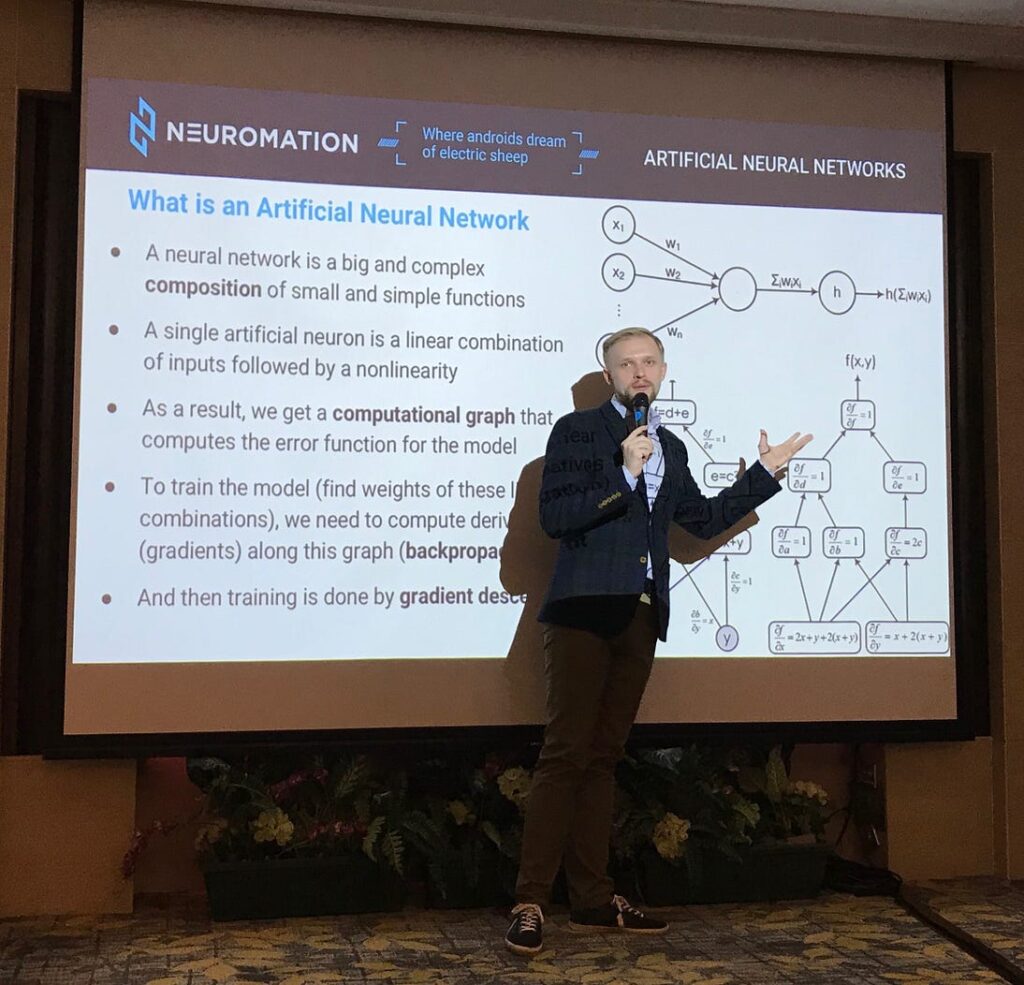

Today, we present a pose estimation model based on the so-called Part Affinity Fields (PAF), a model from this paper that we have uploaded on the NeuroPlatform as a demo. And presenting this model today is Arseny Poezzhaev, our data scientist and computer vision aficionado who has moved from Kazan to St. Petersburg to join Neuromation! We are excited to see Arseny join and welcome him to the team (actually, he joined from the start, more than a month ago, but the NeuroNuggets duty caught up only now). Welcome:

Introduction

Pose estimation is one of the long-standing problems of computer vision. It has interested researchers over the last several decades because not only is pose estimation an important class of problems itself, but it also serves as a preprocessing step for many even more interesting problems. If we know the pose of a human, we can further train machine learning models to automatically infer relative positions of the limbs and generate a pose model that can be used to perform smart surveillance with abnormal behaviour detection, analyze pathologies in medical practices, control 3D model motion in realistic animations, and a lot more.

Moreover, not only humans can have limbs or a pose! Basically, pose estimation can deal with any composition of rigidly moving parts connected to each other at certain joints, and the problem is to recover a representative layout of body parts from image features. We at Neuromation, for example, have been doing pose estimation for synthetic images of pigs (cf. our Piglet’s Big Brother project):

Traditionally, pose estimation used to be done by retrieving motion patterns from optical markers attached to the limbs. Naturally, pose estimation would work much better if we could afford to put special markers on every human on the picture; alas, our problem is a bit harder. The next point of distinction between different approaches is the hardware one can use: can we use multiple cameras? 3D cameras that estimate depth? infrared? Kinect? is there a video stream available or only still images? Again, each additional source of data can only make the problem easier, but in this post we concentrate on a single standard monocular camera. Basically, we want to be able recognize the poses on any old photo.

Top-Down and Bottom-Up

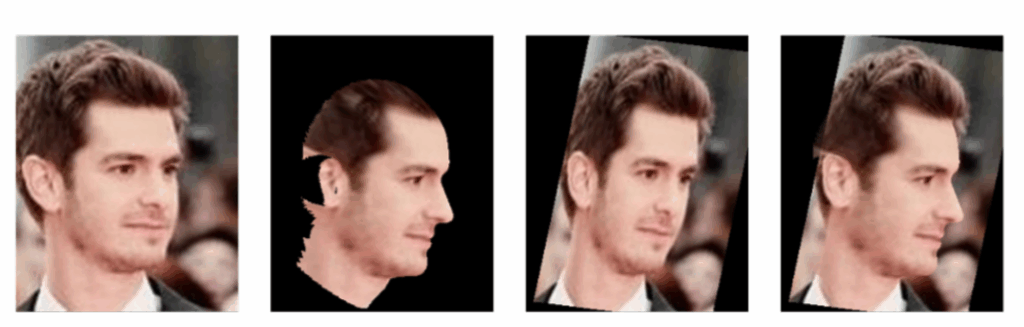

Pose estimation from a single image is a very under-constrained problem precisely due to the lack of hints from other channels, different viewpoints from multiple cameras, or motion patterns from video. The same pose can produce quite different appearances from different viewpoints and, even worse, human body has many degrees of freedom, which means that the solution space has high dimension (always a bad thing, trust me). Occlusions are another big problem: partially occluded limbs cannot be reliably recognized, and it’s hard to teach a model to realize that a hand is simply nowhere to be seen. Nevertheless, single person pose estimation methods show quite good results nowadays.

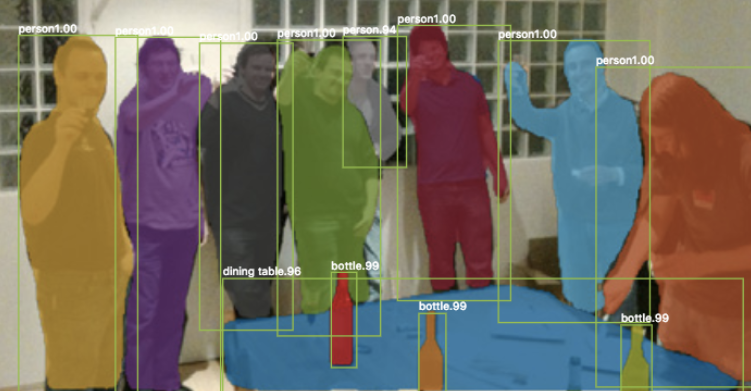

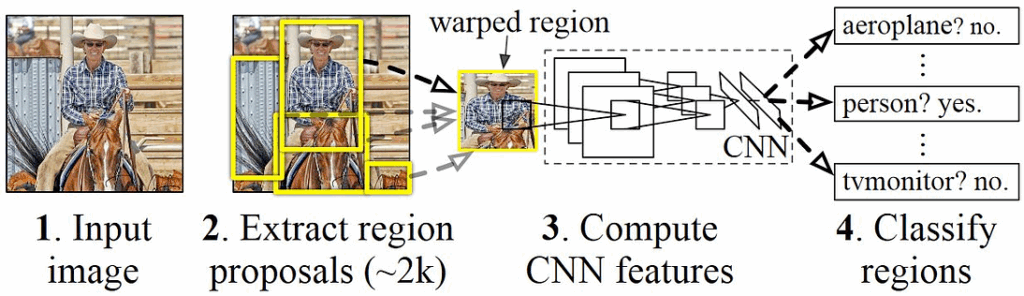

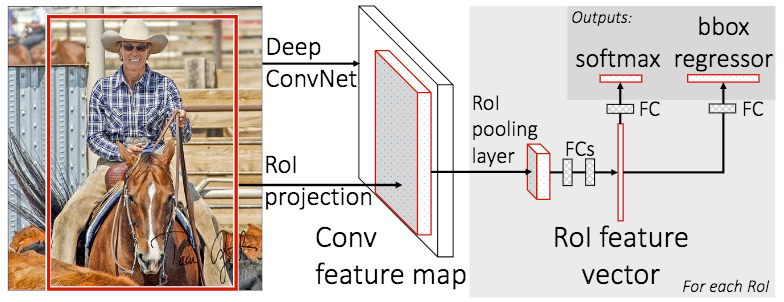

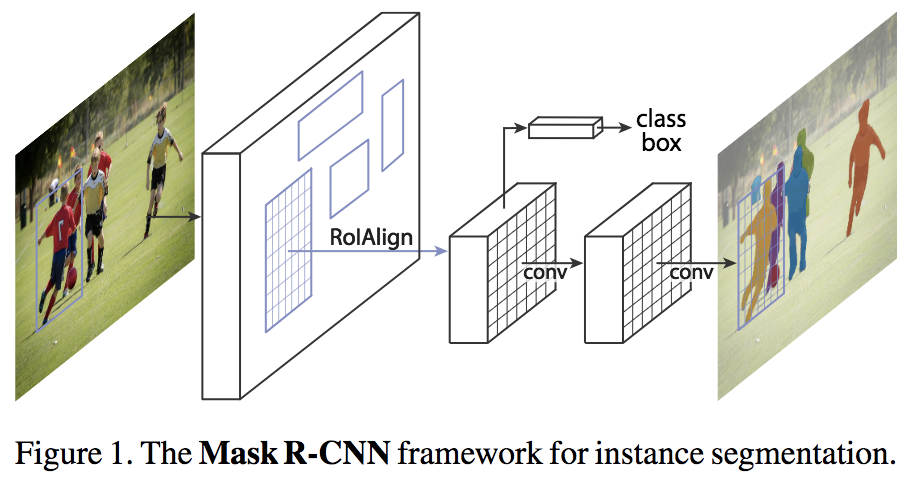

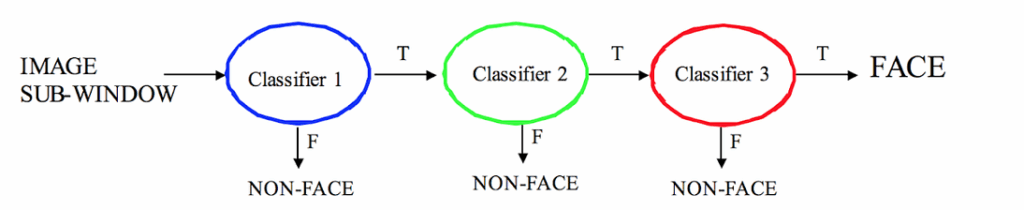

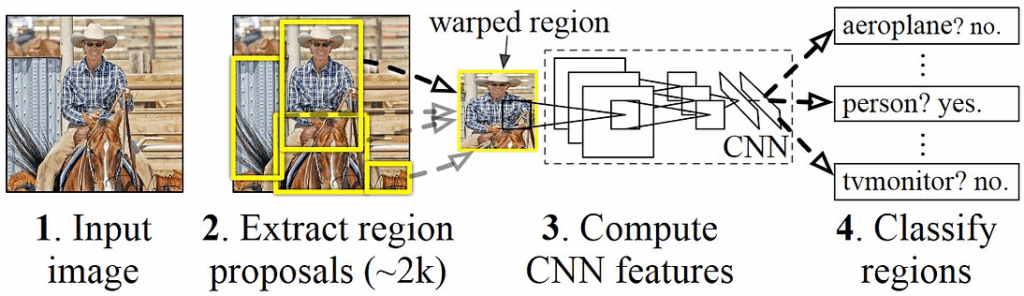

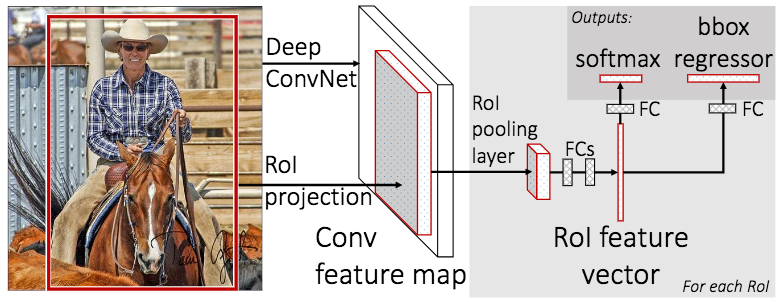

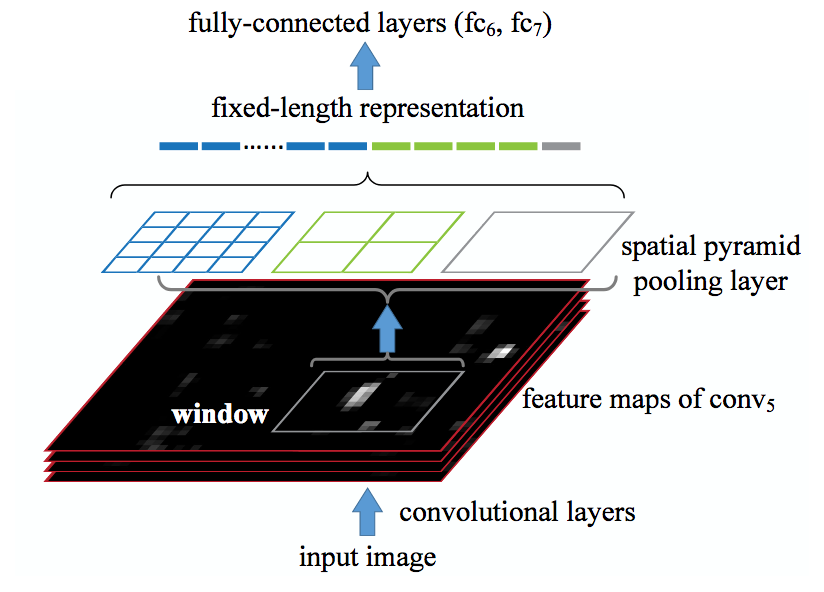

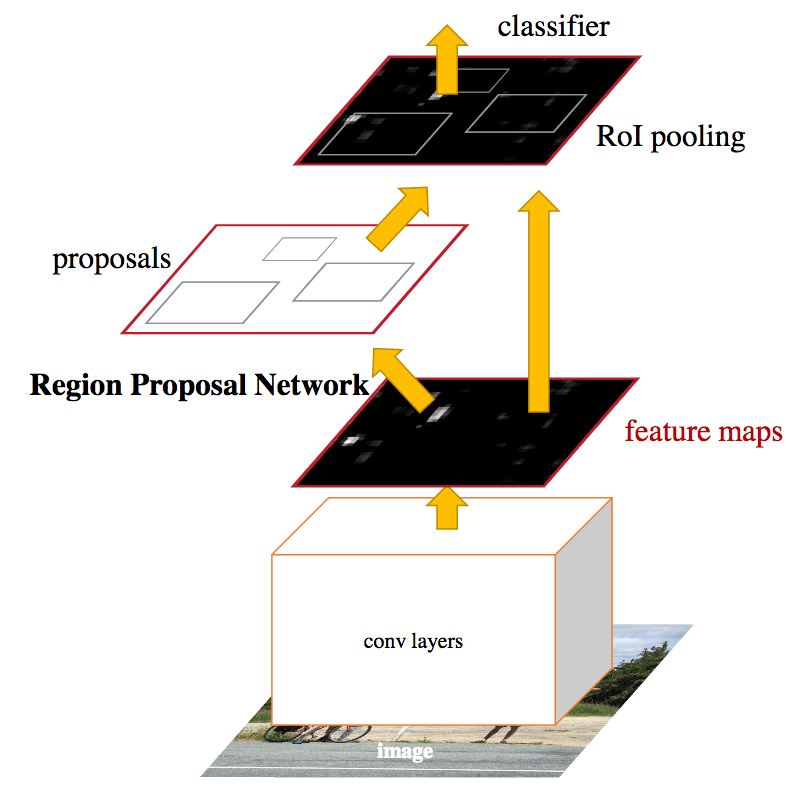

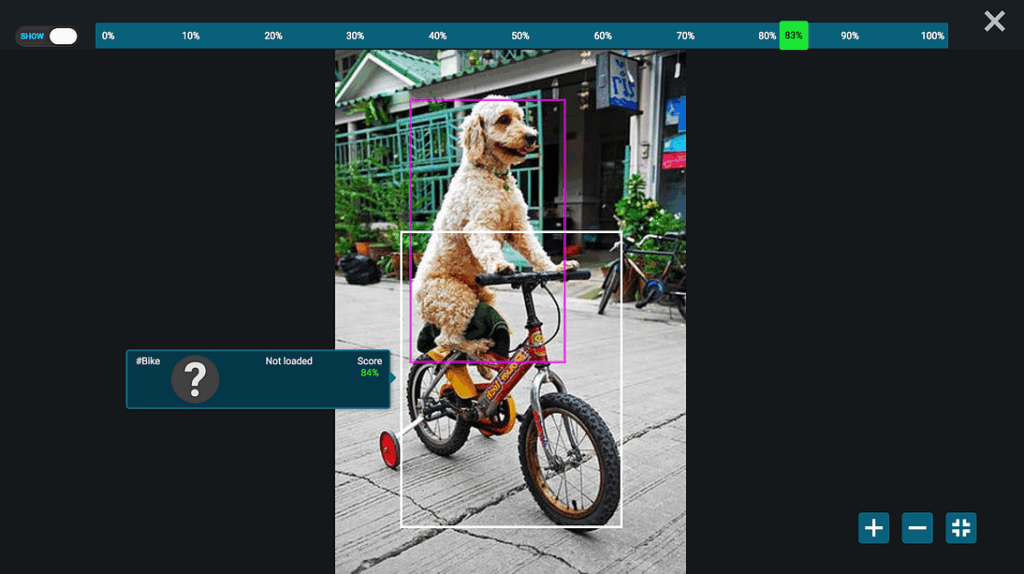

When you move from a single person to multiple people, pose estimation becomes even harder: humans occlude and interact with other humans. In this case, it is common practice to use a so-called top-down approach: apply a separately trained human detector (based on object detection techniques such as the ones we discussed before), find each person, and then run pose estimation on every detection. It sounds reasonable but actually the difficulties are almost insurmountable: if the detector fails to detect a person, or if limbs from several people appear in a single bounding box (which is almost guaranteed to happen in case of close interactions or crowded scenes), the whole algorithm will fail. Moreover, the computation time needed for this approach grows linearly with the number of people on the image, and that can be a big problem for real-time analysis of groups of people.

In contrast, bottom-up approaches recognize human poses from pixel-level image evidence directly. They can solve both problems above: when you have information from the entire picture you can distinguish between the people, and you can also decouple the runtime from the number of people on the frame… at least theoretically. However, you are still supposed to be able to analyze a crowded scene with lots of people, assigning body parts to different people, and even this task by itself could be NP-hard in the worst case.

Still, it can work; let us show which pose estimation model we chose for the Neuromation platform.

Part Affinity Fields

In the demo, we use the method based on the “Realtime Multi-Person 2D Pose Estimation using Part Affinity Fields” paper done by researchers from The Robotics Institute at Carnegie Mellon University (Cao et al., 2017). Here is it in live action:

https://cdn.embedly.com/widgets/media.html?src=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.youtube.com%2Fembed%2FpW6nZXeWlGM%3Ffeature%3Doembed&display_name=YouTube&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.youtube.com%2Fwatch%3Fv%3DpW6nZXeWlGM&image=https%3A%2F%2Fi.ytimg.com%2Fvi%2FpW6nZXeWlGM%2Fhqdefault.jpg&key=a19fcc184b9711e1b4764040d3dc5c07&type=text%2Fhtml&schema=youtube

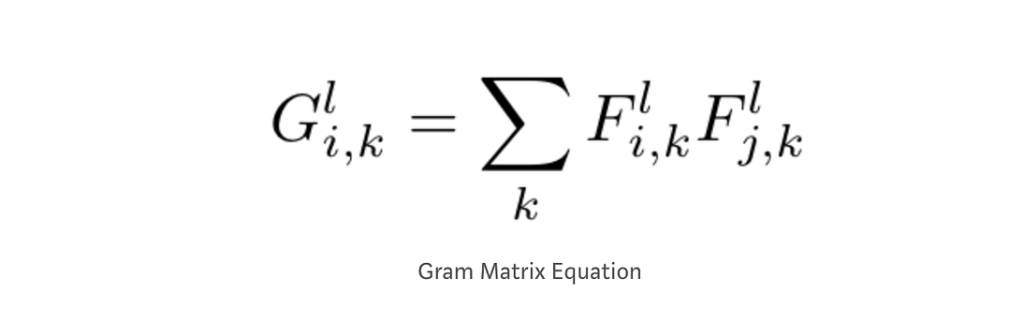

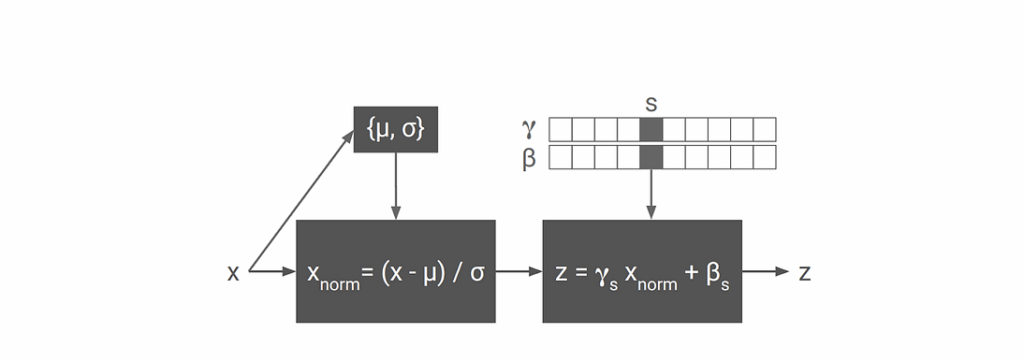

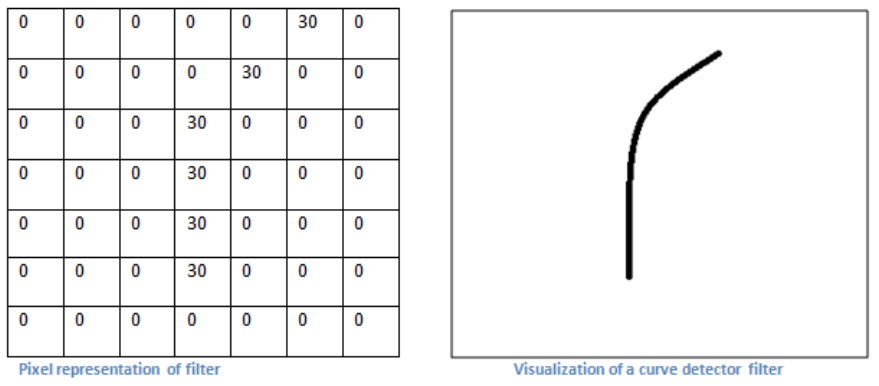

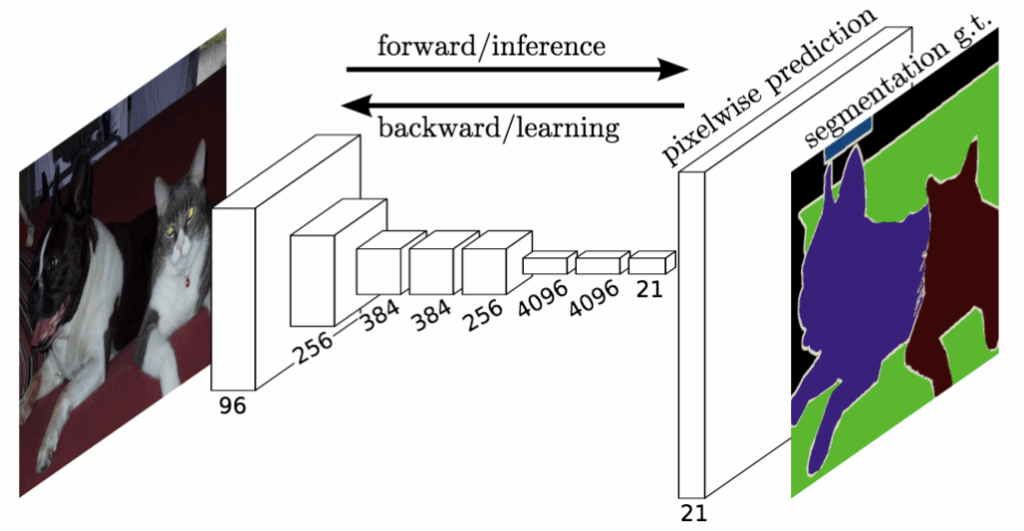

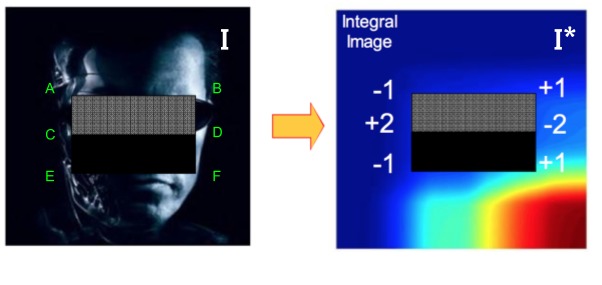

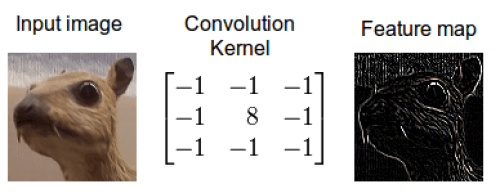

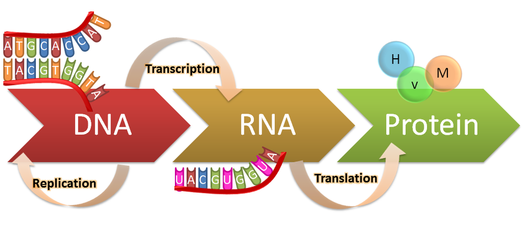

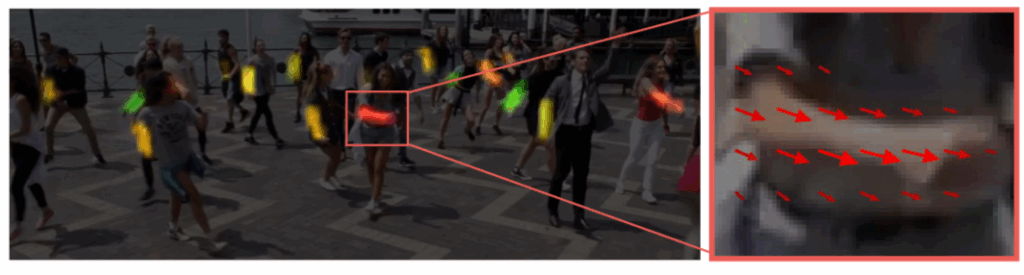

It is a bottom-up approach, and it uses the so-called Part Affinity Fields (PAFs) together with estimation of body-part confidence maps. PAFs are the main new idea we introduce today, so let us discuss them in a bit more detail. A PAF is a set of 2D vector fields that encode the location and orientation of the limbs. Vector fields? Sounds mathy… but wait, it’s not that bad.

Suppose you have already detected all body parts (hands, elbows, feet, ankles etc.); how do you now generate poses from them? First, you must find out how to connect two points to form a limb. For each body part, there are several candidates to form a limb: there are multiple people on the image, and there also can be lots of false positives. We need some confidence measure for the association between each body part detection. Cao et al. propose a novel feature representation called Part Affinity Fields that contains information about location as well as orientation across the region of support of the limb.

In essence a PAF is a set of vectors that encodes the direction from one part of the limb to the other; each limb is considered as an affinity field between body parts. Here is a forehand:

If a point lies on the limb then its value in the PAF is a unit vector pointing from starting joint point to ending joint point of this limb; the value is zero if it is outside the limb. Thus, PAF is a vector field that contains information about one specific limb for all the people on the image, and the entire set of PAFs encodes all the limbs for every person. So how do PAFs help us for pose estimation?

Method overview

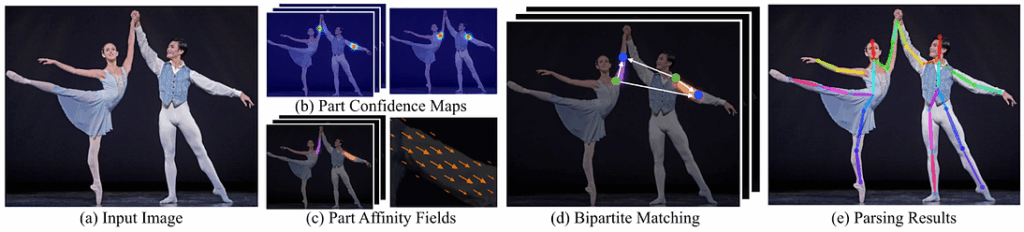

First, let us go through the overall pipeline of the algorithm.

Figure 2 above illustrates all the steps from an input image (Fig. 2a) to anatomical keypoints as an output (Fig. 2e). First, a feedforward neural network predicts a set of body part locations on the image (Fig. 2b) in the form of a confidence map and a set of PAFs that encode the degree of association between these body parts (Fig. 2c). Thus, the algorithm gets all information necessary for further matching of limbs and people (all of this stuff does sound a bit bloodthirsty, doesn’t it?). Next, confidence maps and affinity fields are parsed together (Fig 1d) to output the final positions of limbs for all people on the picture.

All of this sounds very reasonable: we now have a plan. But so far this is only a plan: we don’t know how to do any of these steps above. So now let us consider every step in detail.

Architecture

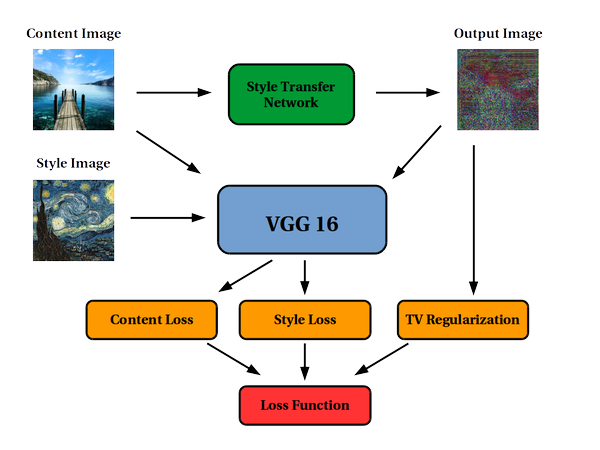

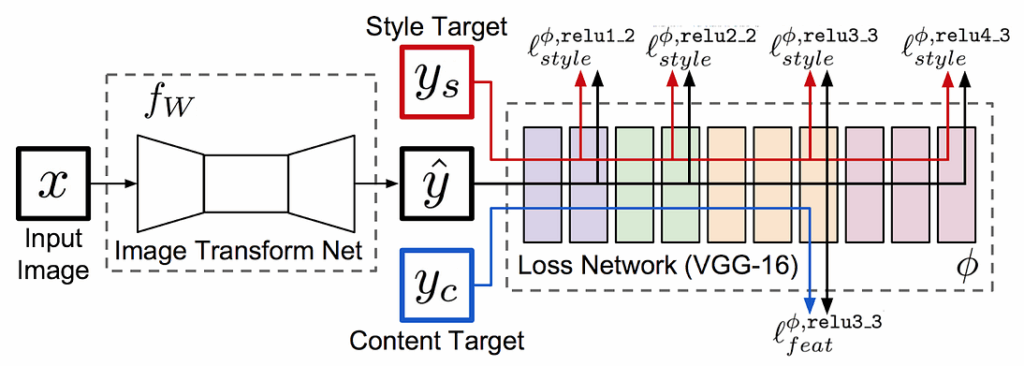

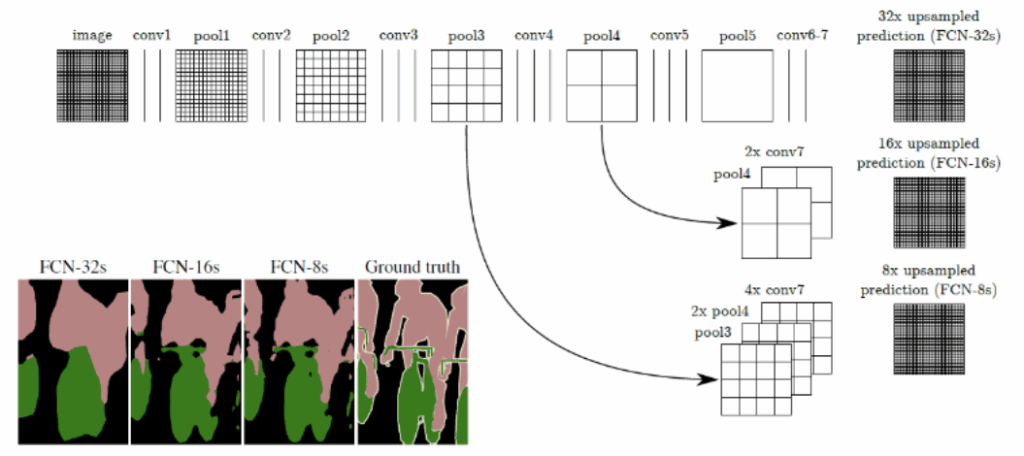

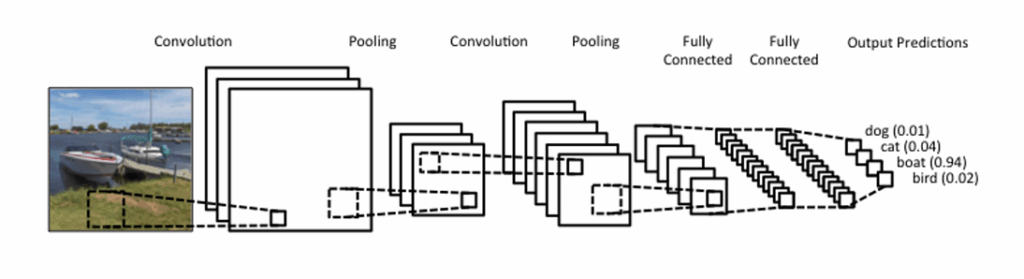

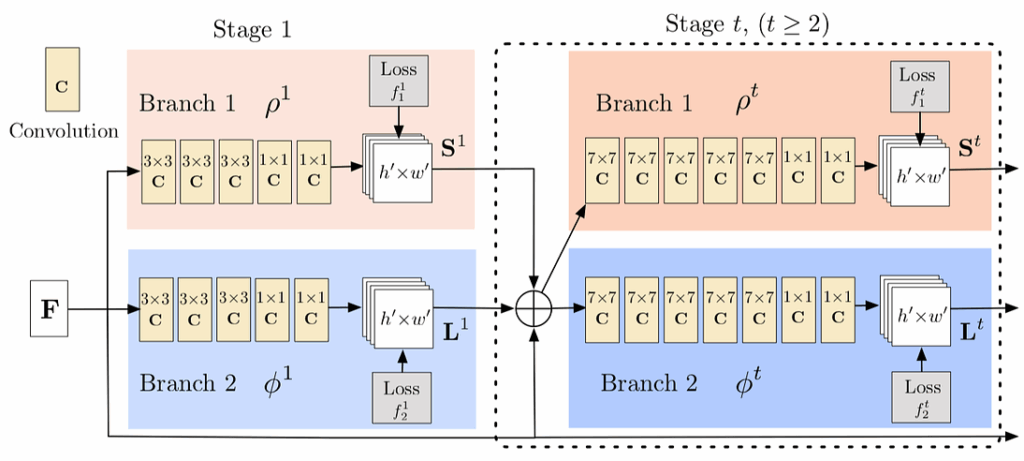

One of the core ideas of (Cao et al., 2017) is to simultaneously predict detection confidence map and affinity fields. The method uses a special feedforward network as a feature extractor. The network looks like this:

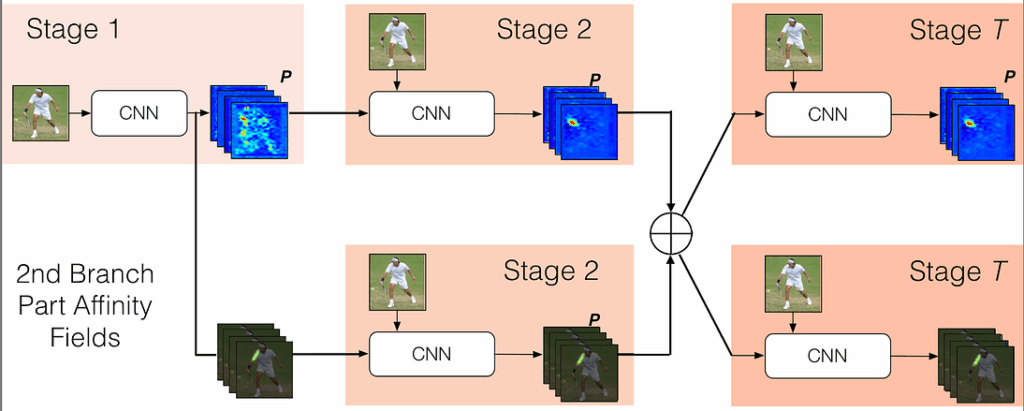

As you can see, it is split into two branches: the top branch predicts the detection confidence maps and the bottom branch is for affinity fields. Both branches are organized as an iterative prediction architecture, which refines predictions over successive stages. The improvement of accuracy of predictions is controlled by intermediate supervision at each stage. Here is how it might look on a real image:

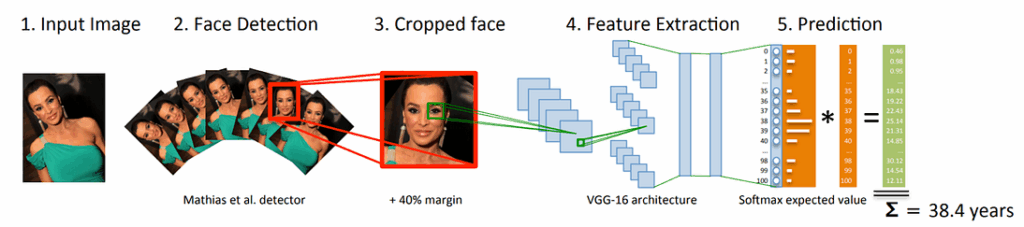

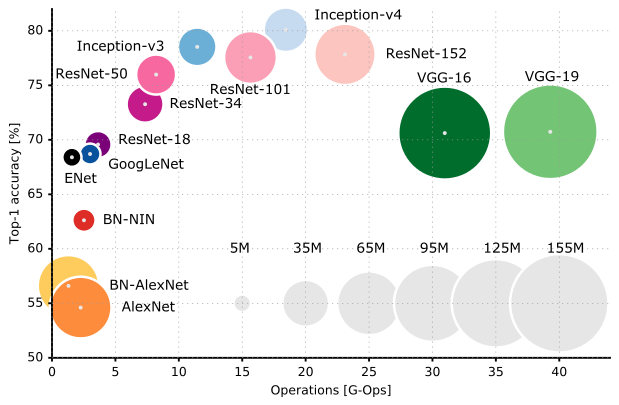

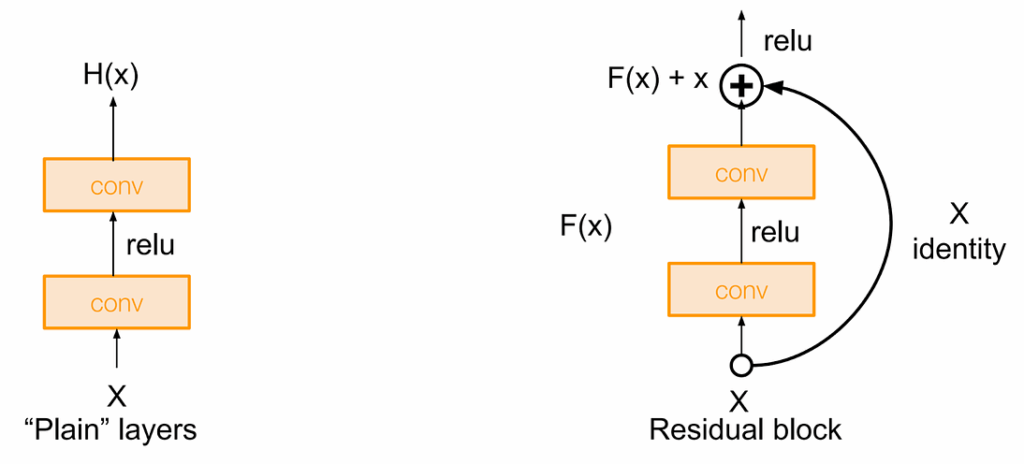

Before passing input to this two-branch network the method uses auxiliary CNN (first 10 layers of VGG-19) to extract an input feature map F. This prediction is processed by both branches, and their predictions concatenated with initial F are used as input for the next stage (as features).

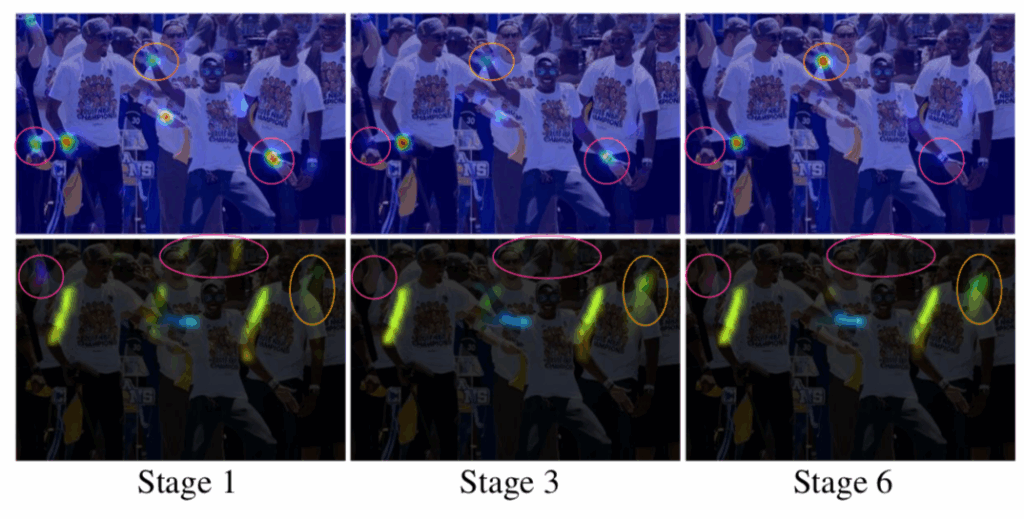

This process is repeated on every stage, and you can see the refinement process across stages on Figure 4 above.

From Body Parts to Limbs

Take a look at Figure 5 below, which again illustrates the above-mentioned refinement process:

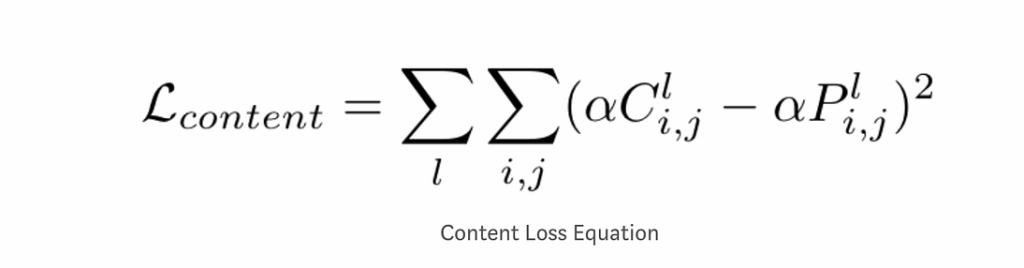

At the end of each stage, the corresponding loss function is applied for each branch to guide the network.

Now consider the top branch; each confidence map is a 2D representation of our confidence that each pixel belongs to a particular body part (we remind that “body parts” here are “points” such as wrists and elbows, and, say, forearms are referred to as “limbs” rather than “body parts”). To get body part candidate regions, we aggregate confidence maps for different people. After that, the algorithm performs non-maximum suppression to obtain a discrete set of parts locations:

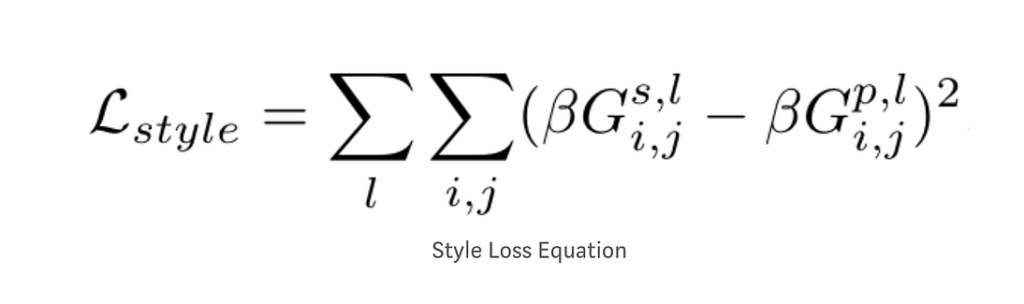

During inference, algorithm computes line integrals over all the PAFs along the line segments between pairs of detected body-parts. If the candidate limb formed by connection of certain pair of points is aligned with corresponding PAF then it’s considered as a true limb. This is exactly what the bottom branch does.

From Limbs to Full Body Models

We now see how the algorithm can find limbs on the image between two points. But we still cannot estimate poses because we need the full body model! We need to somehow connect all these limbs into people. Formally speaking, the algorithm has found body part candidates and has scored pairs of these parts (integrating over PAFs), but the final goal is to find the optimal assignment for the set of all possible connections.

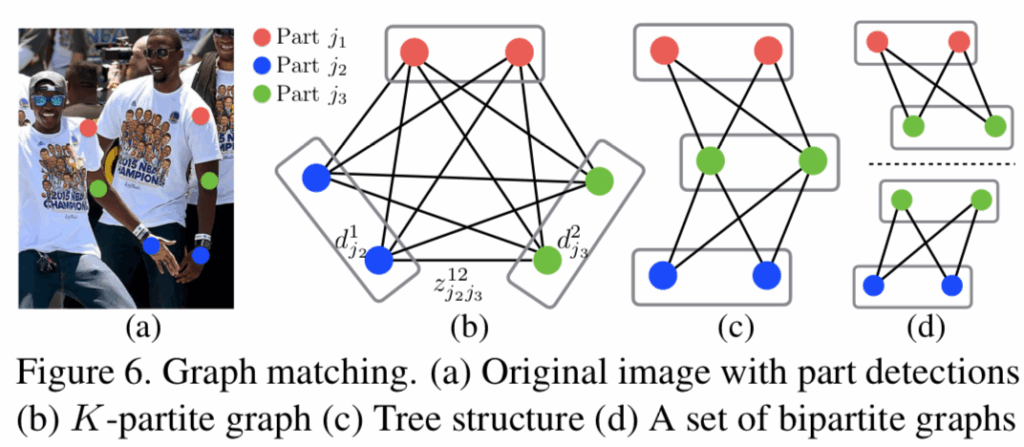

Formally speaking, this problem can be viewed as a k-partite graph matching problem, where nodes of the graph are body part detections, and edges are all possible connections between them (possible limbs). Here k-partite matching means that the vertices can be partitioned into k groups of nodes with no connections inside each group (i.e., vertices corresponding to the same body part). Edges of the graph are weighted with part affinities. Like this:

A direct solution of this problem may be computationally infeasible (NP-hard), so (Cao et al., 2017) propose a relaxation where the initial k-partite graph is decomposed into a set of bipartite graphs (Fig. 7d) where the matching task is much easier to solve. The decomposition is based on the problem domain: basically, you know how body parts can connect, and a hip cannot be connected to a foot directly, therefore we can first connect hip to knee and then knee to foot.

That’s all, folks! We have considered all the steps in the algorithm that can retrieve poses from a single raw image. Let us now see how it works on our platform.

Pose Estimation Demo in Action

There are, as always, a few simple steps to run this algorithm on our image of interest:

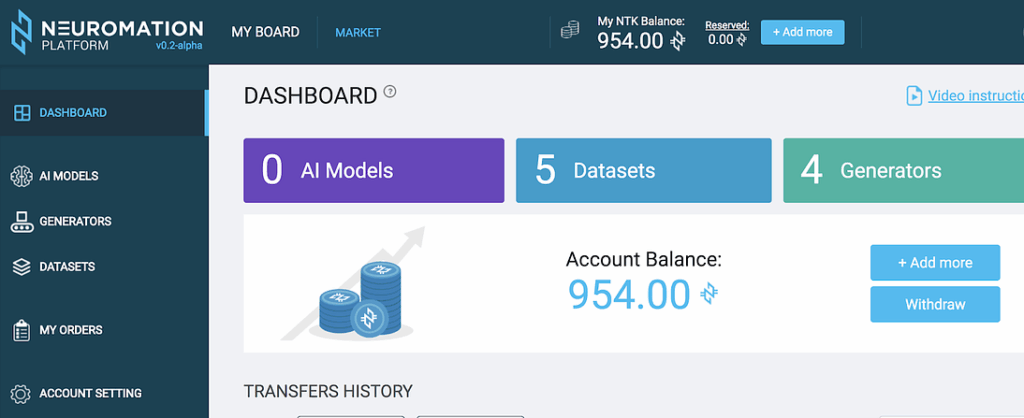

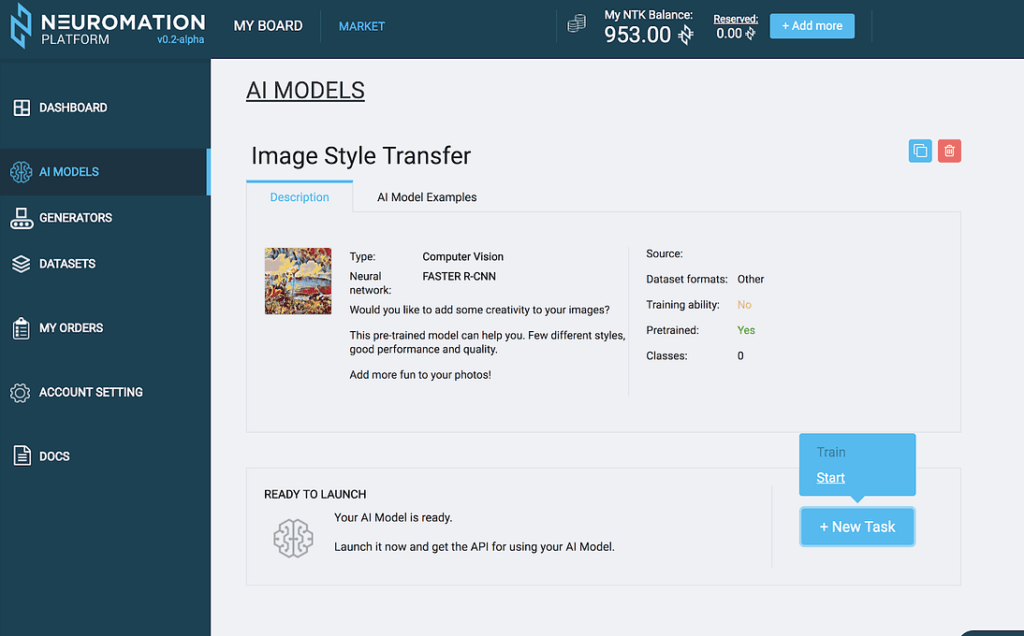

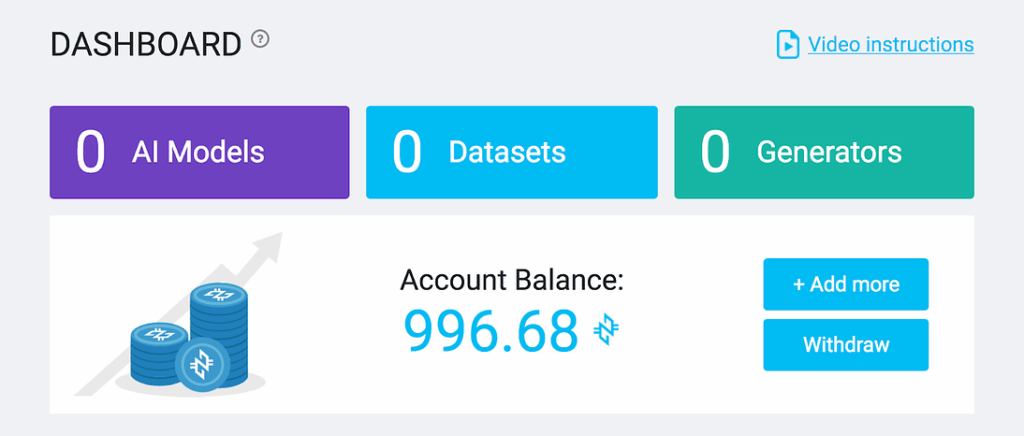

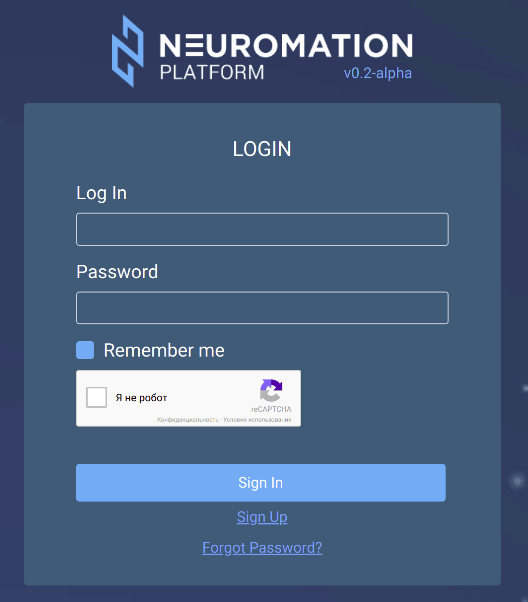

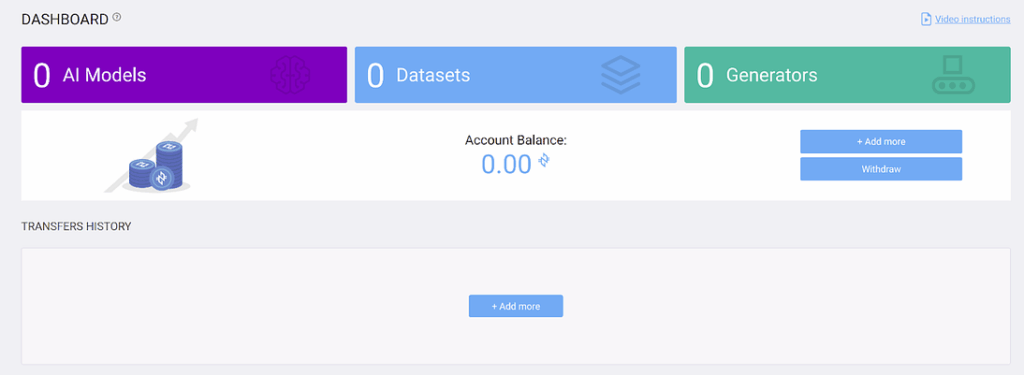

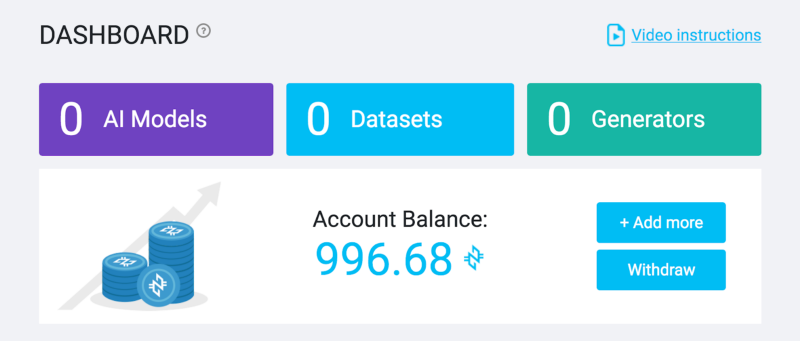

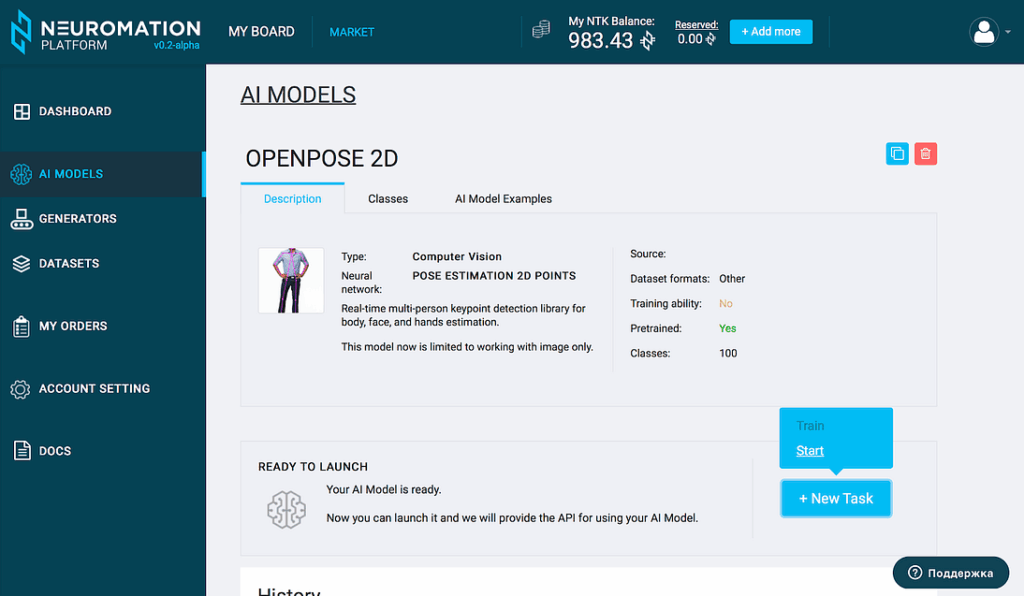

- Login at https://mvp.neuromation.io

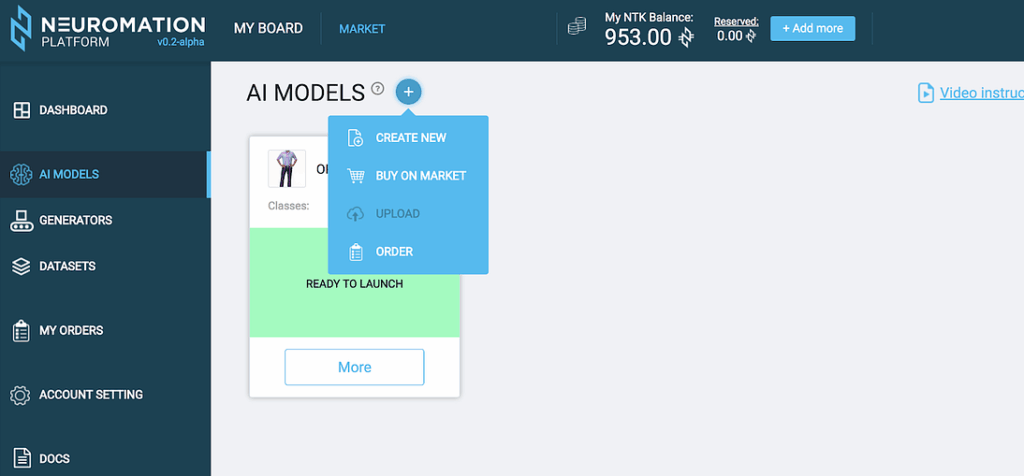

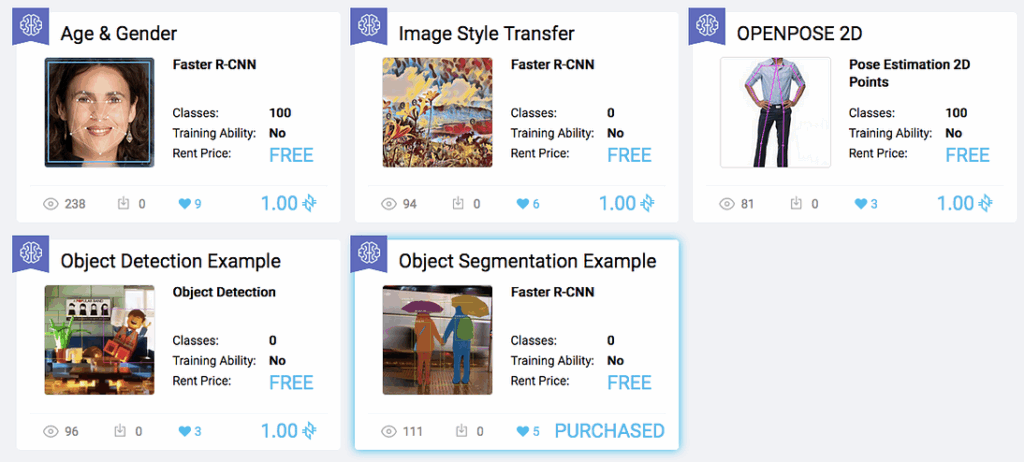

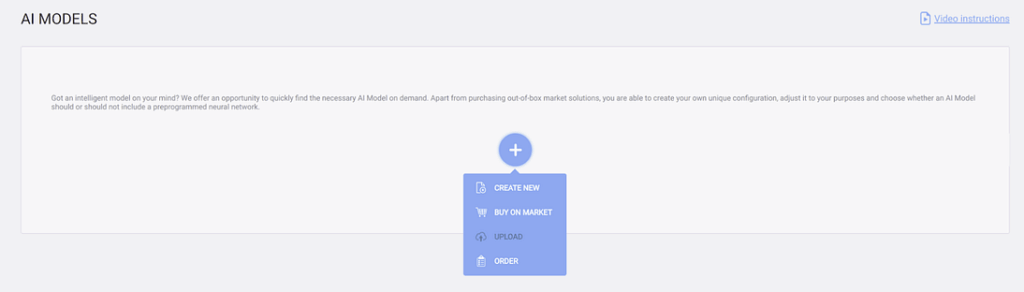

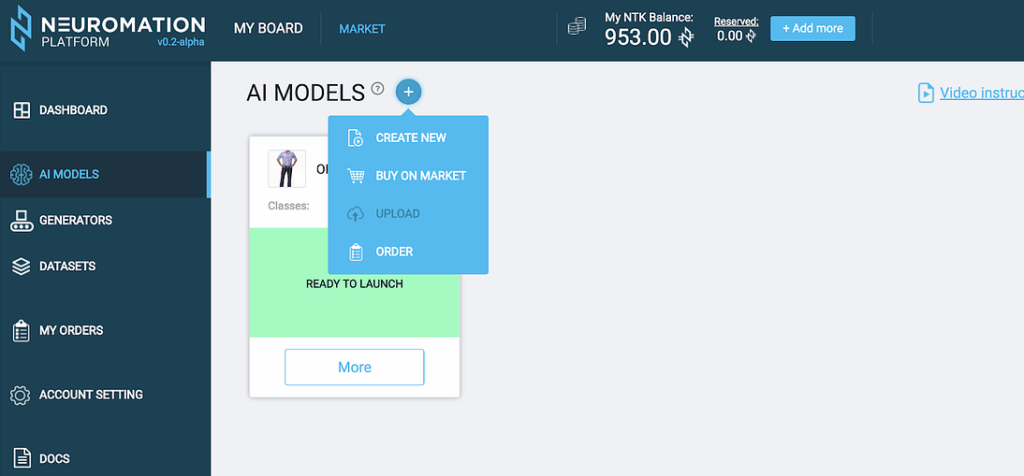

- Go to “AI models”

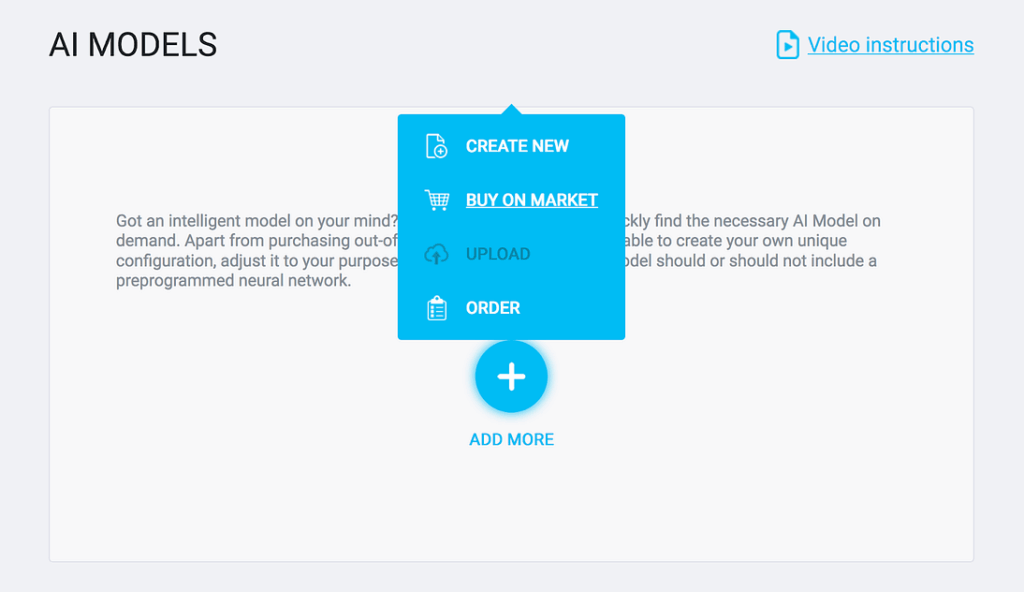

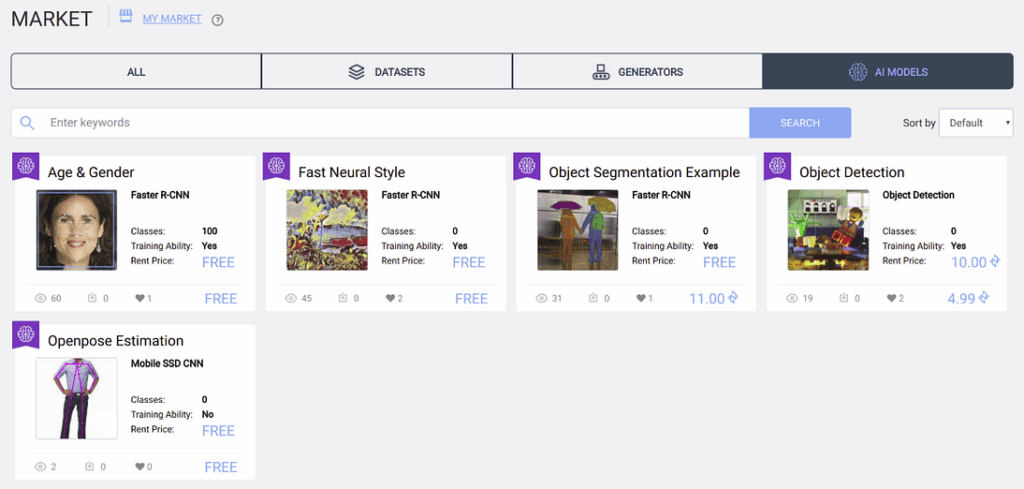

- Click “Add more” and “Buy on market”:

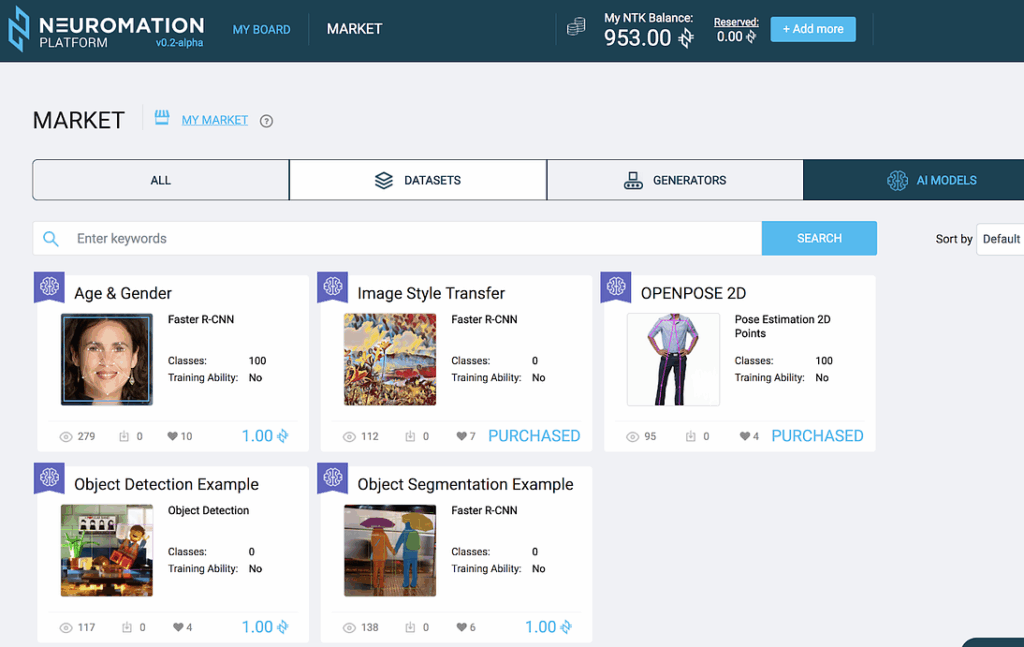

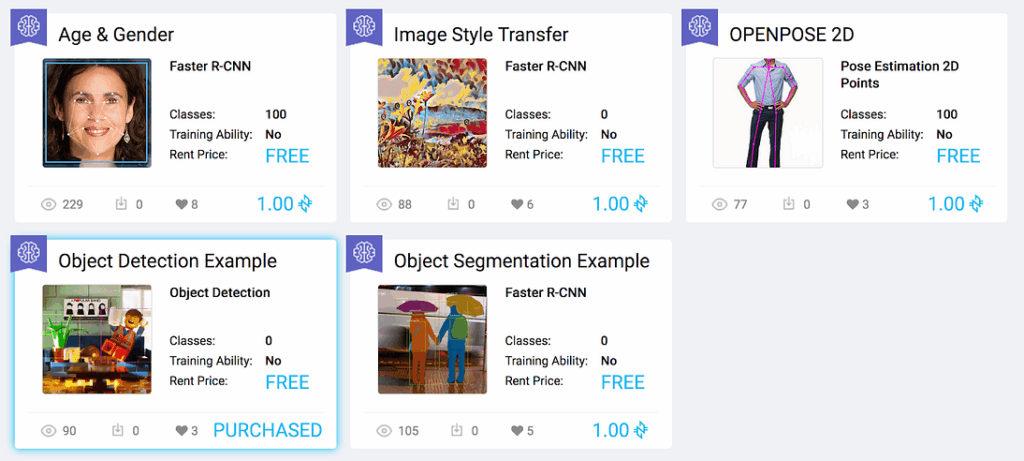

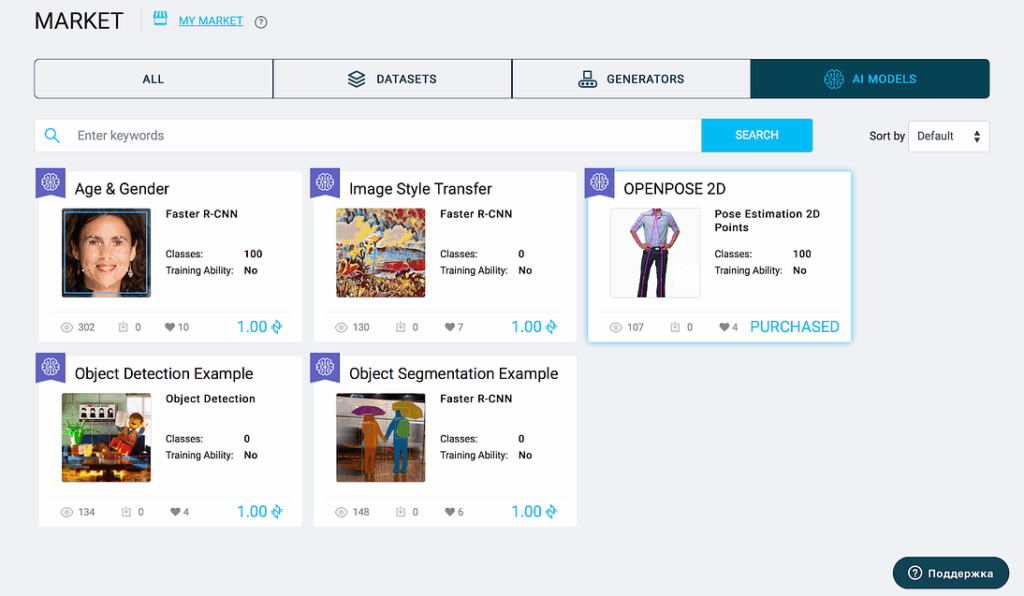

4. Select and buy the OPENPOSE 2D demo model:

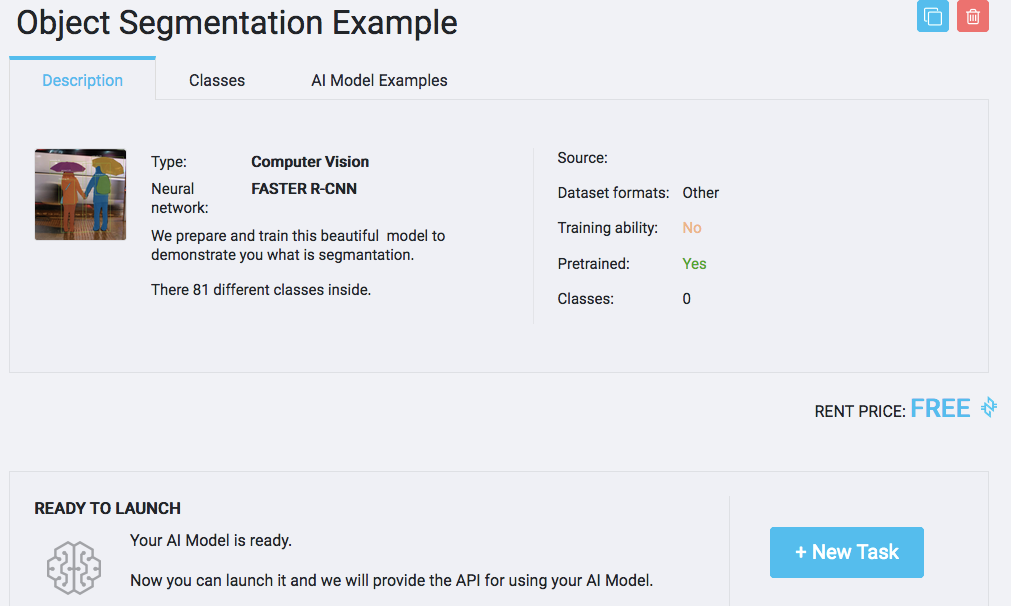

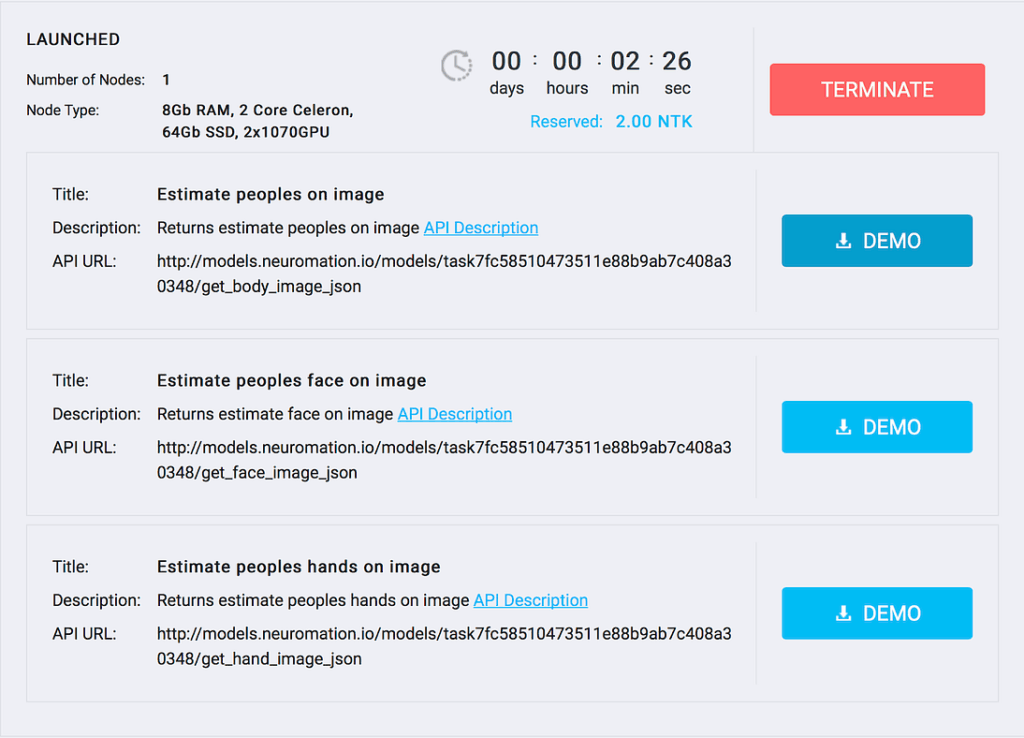

5. Launch it with “New Task” button:

6. Choose the Estimate People On Image Demo:

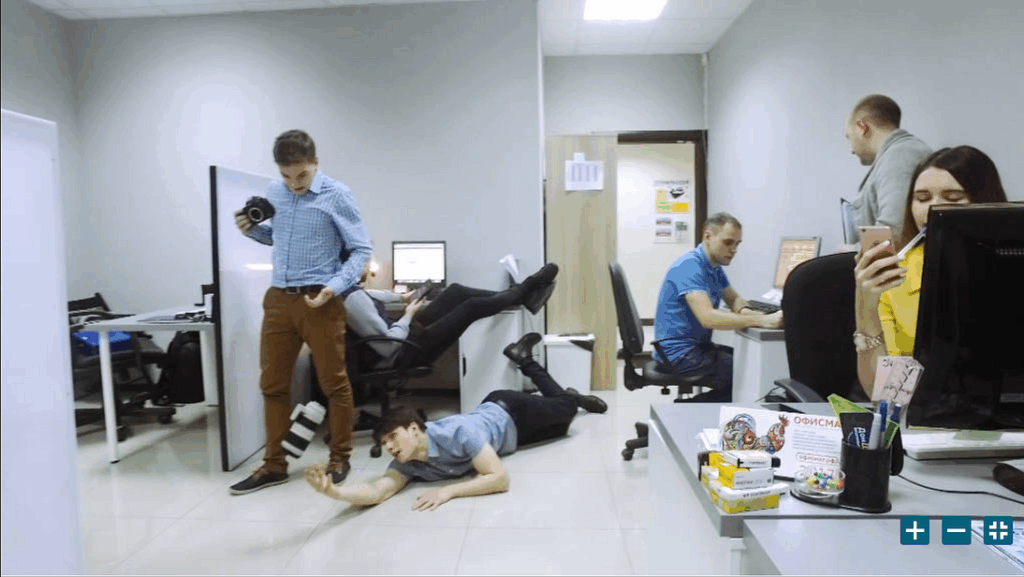

7. Try the demo! You can upload your own photo for pose estimation. We chose this image from the Mannequin Challenge:

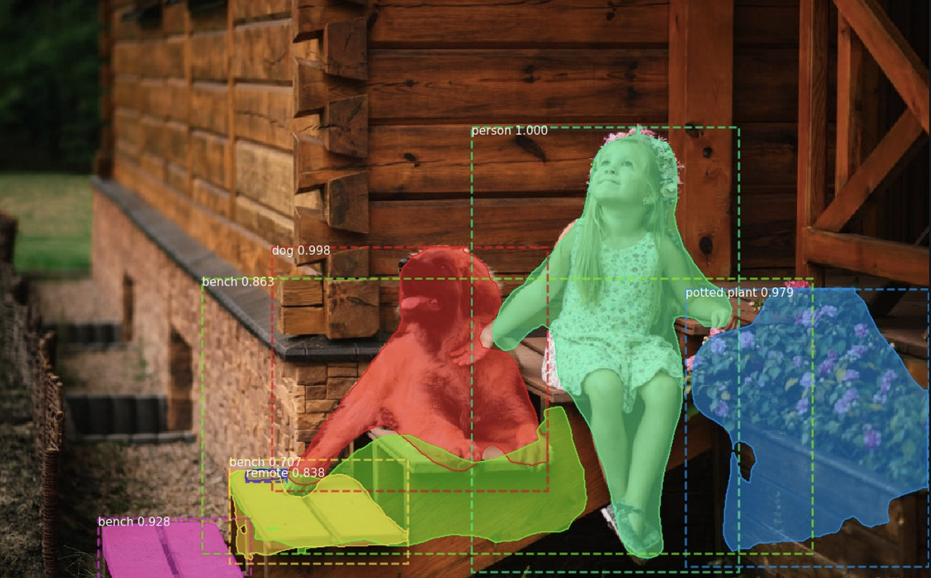

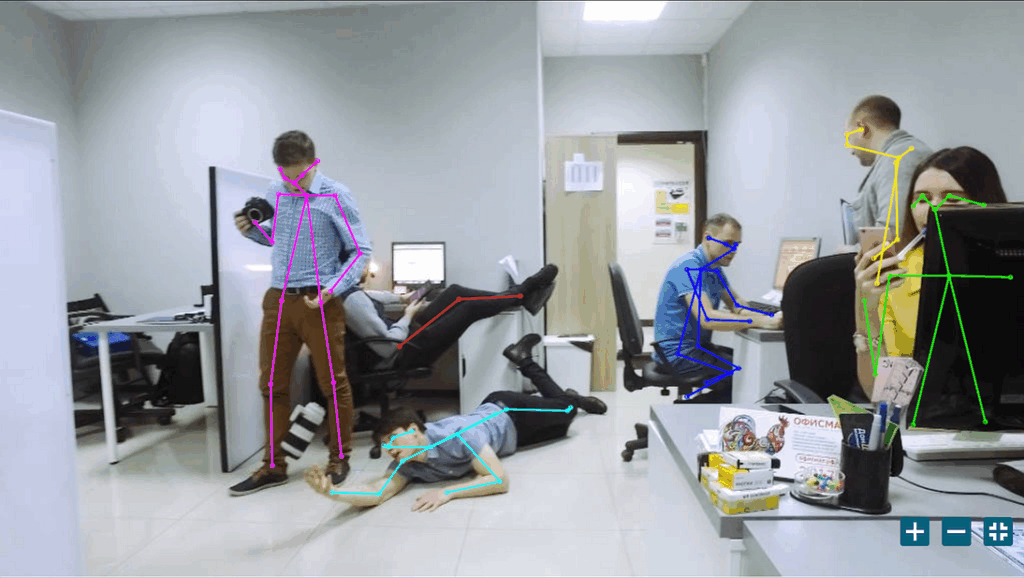

8. And here you go! One can see stick models representing poses of people on the image:

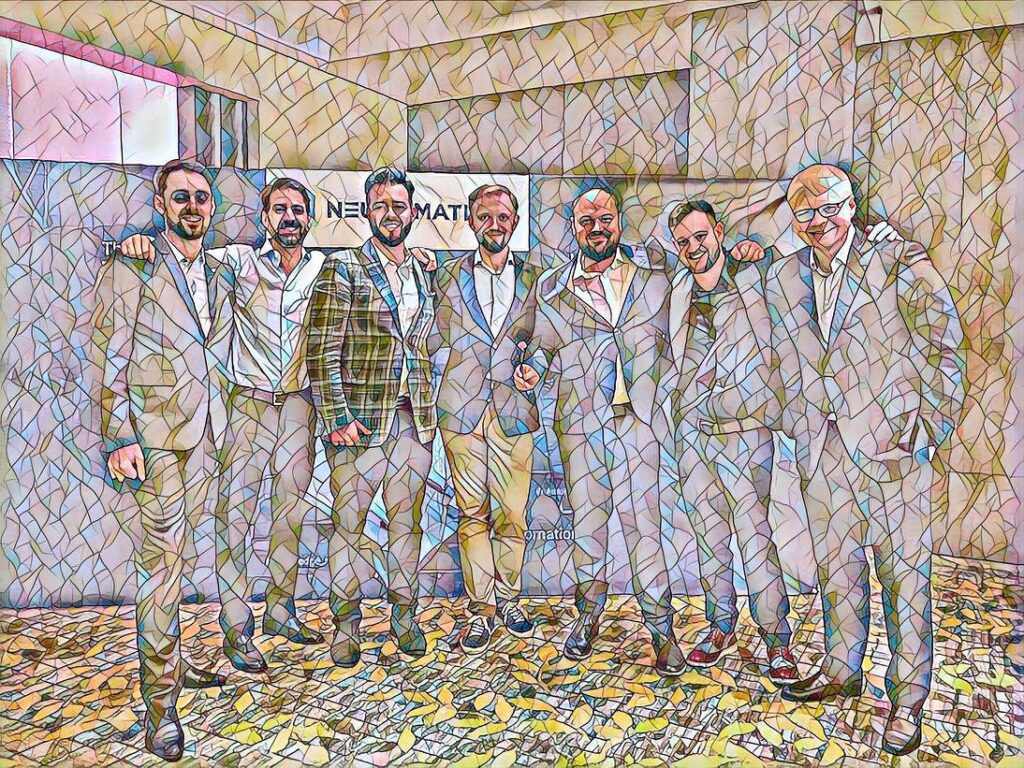

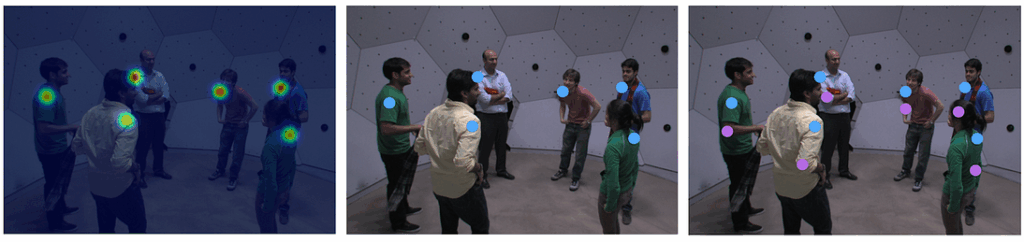

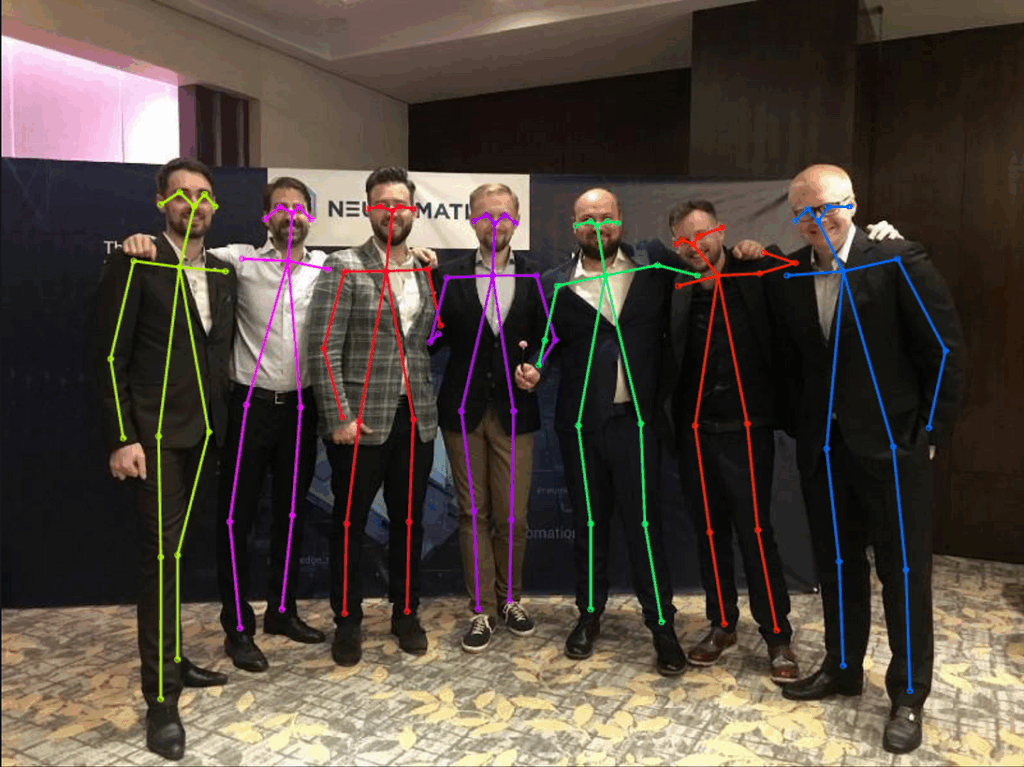

And here is a picture of Neuromation leadership in Singapore:

The results are, again, pretty good:

Sergey Nikolenko

Chief Research Officer, Neuromation

Arseny Poezzhaev

Researcher, Neuromation